Recognizing a Language Without a Dictionary – A Simple Example of the N-Gram Method

Is it even possible to tell what language a text is written in (apart from the most common ones) without looking it up in dictionaries? Computational linguistics has a clear and simple method for doing this.

A person can often recognize the language in which a text is written from just a few sentences and without the aid of a dictionary. The letters and symbols reveal which language area – e.g. Western European, Greek, Russian, Indian or Asian – the text belongs to. Diacritical marks such as “é, è, ê, Ł, ň” and punctuation marks such as “!, ?,¿, ؟, ᠃,፣” provide further clues.

A computer works differently. It doesn’t need a dictionary either, but it doesn’t care about an alphabet or the meaning of a single character. It simply counts the occurrences of each character for the individual languages or even dialects in a large amount of training data from a wide variety of domains, calculates different percentages and stores these statistics as a kind of fingerprint. In German, for example, there are many “e, n” and few “y, x, q“; in English there are “e, t, a” and “x, q, z“. Other features such as the proportion of upper and lower case letters, spaces, punctuation marks and the distribution curve of sentence and word lengths refine the linguistic fingerprint. For language recognition, a fingerprint is also calculated from the unknown text and compared with the existing ones. The closest match shows the language being searched for.

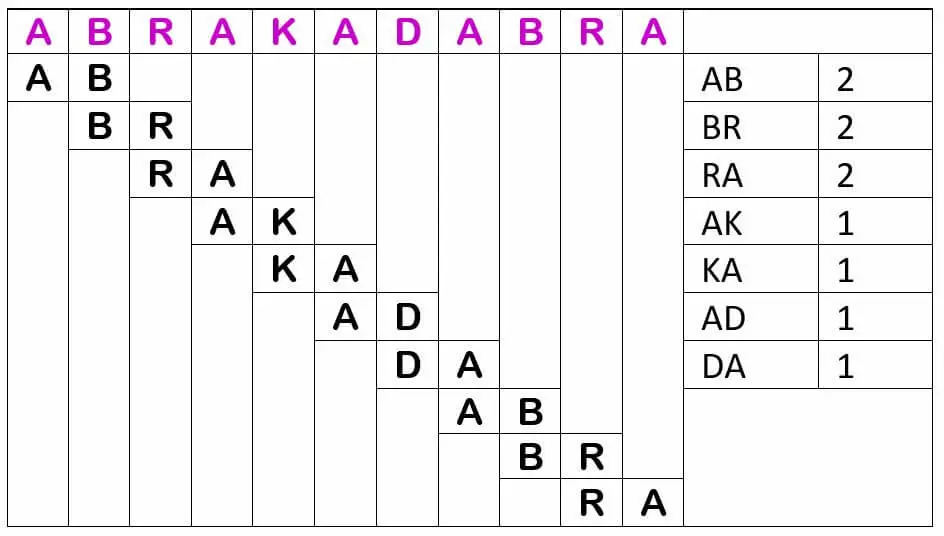

However, the computer not only looks at individual characters (unigrams), but also at two adjacent characters (bigrams), regardless of whether they are alphabet characters, spaces or punctuation marks. It works with overlapping bigrams, i.e. the first bigram starts at position 1 and contains the first and second characters, the second bigram starts at position 2 and contains the second and third characters, and so on.

Again, depending on the language, there are typically more frequent combinations, especially with word prefixes and suffixes. In German these are “er, en, el, be, ge, ab, an, zu, st, kl, kr, br, pr, kr, bl, ei, ch, ig“, in English “un, in, il, im, ir, re, ex, or“. Further information is provided by the trigrams; in German these are “sch, str, ver, auf, aus, bei, ein, ent, her, hin, vor, zer, ung, nis, tum, tät, gen, ben, hen, sen, kel, pel, kel, der, ter, ber, ler, sam, bar“, in English “dis, non, mis, ian, ism, ive, sis“. Next come the 4-grams and so on. The more precise the fingerprint of a language, the easier it is to distinguish closely related languages.

As the N-gram method is independent of language and alphabet, it is also used to decode ciphers. It is also well suited for quickly and easily making a statement about the content of a text. The N-grams are not formed at character level, but at word level. The reference here is a constructed text that contains all key words and expressions and, in particular, all paraphrases for a desired and predefined topic, thus providing an “ideal” fingerprint statistic. When compared with this, e.g. e-mails or forum posts with “dangerous” content on the subject of terrorism or drug cultivation can be found.

Speech recognition has become very important in our globalized world. It is used, for example, for web content and multinational archives.

Computer scientist and computer linguist

Ulrike is a computer scientist and computer linguist. The thematic focus of her blog posts is on the comprehensibility and usability of the human-machine interface.

More articles from Content in Context

|

|